Mr Coe et moi

It’s been over a year since I was laid up at home, recuperating from an encounter with a campervan while riding a bicycle. I’d come off second best, breaking my collarbone, although the campervan didn’t come out of it too well either. I’d spent a few days in hospital, but the medical assessment was that it wouldn’t be necessary to operate, that the fractured bone would heal itself.

By spring of this year I thought I was fully fixed but, by that point, I hadn’t got back on my bike or done much exercise at all since my fall from grace. It gradually became apparent that self repair hadn’t been entirely successful, my shoulder painful even when not moving. The very last thing that the consultant had said as he discharged me had been something like “If your shoulder gives you any problems in the future, just get in touch.” At the time I thought that’s just something nice he says to everyone, but about a month ago I did just that.

And now I'm laid up at home again, recuperating from an operation on my collarbone performed by the consultant last week. I’m bruised again but this time I’ve come out on top. Without question there are problems with the NHS, but my experience of it over the last 15 months has been that of a smooth-running machine, and I have nothing but praise for everyone I have encountered working at the Royal Infirmary.

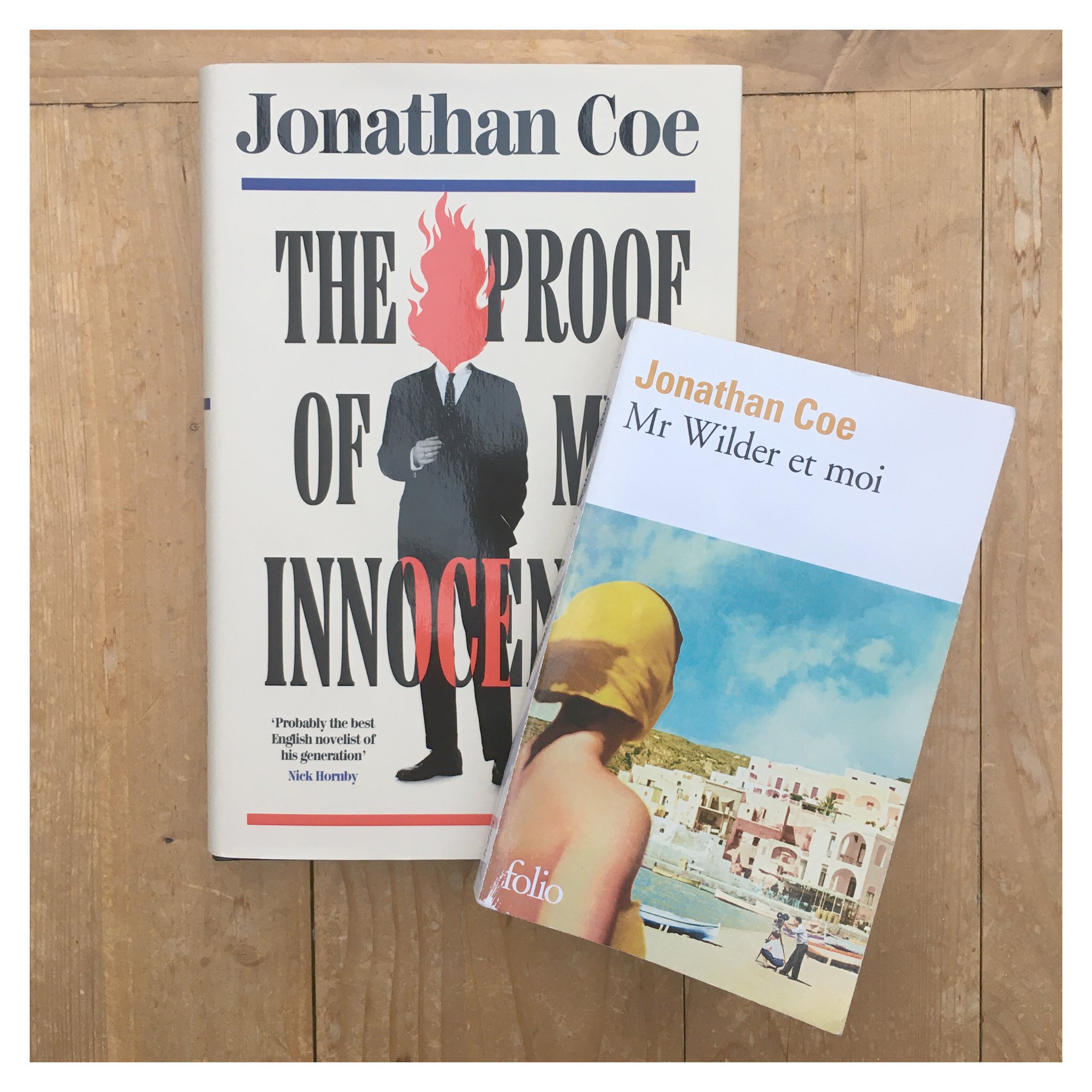

During that first period of recuperation - autumn 2023 - I read some of the novels of Jonathan Coe: The Accidental Woman, A Touch of Love, The Dwarves of Death, Expo 58, The House of Sleep, What A Carve Up!, and Mr Wilder & Me. The first three were new to me, the others re-reads, I’ve now lost count of often I’ve returned to What A Carve Up!

Jonathan Coe’s 15th novel The Proof of My Innocence was published a few weeks before I was admitted to hospital this time around. There have been a few sniffy reviews, Finn McRedmond in the Financial Times describing it as a “tedious polemic” and Claire Allfree writing on the Tortoise website, concluding that Coe is “losing his edge as a social satirist”. (I do wonder if Ms Allfree has read any further than the jacket copy.) However, these are outliers, and, for my part, my only disappointment is that having raced through the book’s 352 pages in a few hours, I will now likely have to wait another two years for Coe’s 16th novel.

In the meantime, as a distraction while I was waiting to be called to the operating theatre last Wednesday, I started listening to the audiobook. This proved more difficult than it need have been. In the waiting room there was a large TV showing Good Morning Britain, although why, I don’t know as no one seemed to be watching. Surprisingly - surprising to me at any rate - one of the presenters was Ed Balls. Balls used to be Chief Economic Adviser to the UK Treasury and yet here he was at 7:15am on a cold December morning interviewing a woman who was charging members of her own family £200 a head for Christmas dinner at her house, includes a glass of champagne, children under the age of 16 free. With this going on it was difficult to concentrate on Coe’s political crime story. Never mind that the murder victim, was on the verge of uncovering evidence of a plot to sell off the NHS, the woman charging £200 for her own family to eat Christmas Dinner sounded herself like a grotesque post-Thatcherite character straight from the pages of The Proof of My Innocence.

I do read other authors. This year (so far, still three weeks to go!) I’ve read 65 books, mostly novels and probably 60 authors represented there. But I love Jonathan Coe’s writing. He manages to combine humour with state of the nation commentary in a way that no one else has done over the last thirty years.

However, Coe’s 2020 novel Mr Wilder & Me doesn’t fall into that category. Here he combines gentle humour with his love of cinema, and in particular his love of the films of the great director Billy Wilder. The story is told through the eyes of Calista, a Greek teenager who meets Billy Wilder by chance in Hollywood and ends up working as a translator for him on the production of his penultimate film, Fedora. This won’t spoil the book for anyone who hasn’t read it, but the middle section is in the form of a film script of Wilder’s early life and, for me, is one of the most moving pieces of writing I have ever read. Taken as a whole, the book is a love letter to a golden age of cinema long since gone.

Prior to going into hospital for this operation, I decided that, during the 3-4 weeks recuperation period, I’d “do something useful” like learn a language. I studied French at school to Higher grade but that was a while back. Later, I muddled my way through three years of living in Luxembourg but even that wasn’t yesterday. So a refresh / upgrade / whatever might be in order. I quickly discovered that Duolingo has its limitations. “The cat is eating the croissant” isn’t a phrase I can imagine using very often but yet that came up in the first lesson.

But then I remembered that all of Jonathan Coe’s books have been translated into French (as well as many other languages). So I bought a second hand copy of Mr Wilder et moi, translated by Marguerite Capelle. I’m now 120 pages in and it turns out my French comprehension isn’t that bad. Admittedly I’ve read it twice before in English and any words I don’t know, I’m just guessing at from context. I’m quietly pleased with myself and thinking that after this, I’ll have a stab at Flaubert.

But not only that, and this is possibly because I’m having to read it more slowly than before, I’m picking up on way more than I did on the first two passes. It’s a hugely enjoyable experience. Whether in English, French or any of the other seven languages to which it has been translated, I can’t recommend Mr Wilder & Me enough. It really is le roman parfait.