Books of the Year 2023

I’ll read anything, even Waitrose Weekend, it always pays to keep abreast of the latest development in eggs florentine recipes. But books are where it’s at, like Jez in Peep Show, I adore to read.

Kicking off in January with Margaret Drabble’s 1967 semi-autobiographical novel Jerusalem the Golden (bought in Tills Bookshop for its Crystal Tipps-eque cover), so far I’ve got through 60 books this year. Could do better, as my school reports often said, and in previous years I have read more by volume. But there have been some door-stoppers in there: Barnaby Rudge (Charles Dickens, 1841), Still Life (Sarah Winman, 2021) and continuing the Peep Show theme, a favourite of Super Hans, Barchester Towers (Anthony Trollope, 1857). “Ecclesiastical politics when you’re high. These guys really knew how to do a fucking number on each other.”

So, to my six books of the year. Criteria, published for the first time or in paperback in 2023 or, in one case, late 2022, no one’s counting.

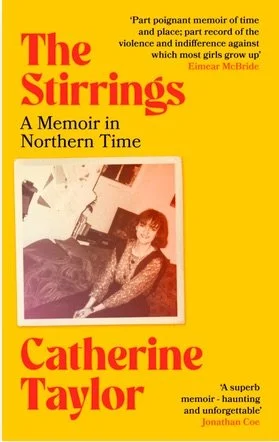

The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 229 pp.

A coming of age memoir set in Sheffield of the late 1970s and 1980s could have been all Mr Kipling’s Bakewell tarts, what was then acceptable but now scarcely believable racist language, weren’t the Human League fab (they were / still are). And there is a bit of that, these three on pages 58 & 59.

But, in what is her first book, Catherine Taylor consummately blends personal stories - the separation of her parents, a disastrous holiday in France with her mother, the effects of a debilitating illness, a later tragedy - with larger events. The spectre of the Yorkshire Ripper hangs heavy throughout, and the Falklands war, miners’ strike, Hillsborough disaster and Greenham Common protests - which as a teenager Taylor took part - all serve as marker points as she crosses into adulthood.

As Jonathan Coe says on the cover, a “haunting and unforgettable” debut.

Peter Womersley by Neil Jackson Liverpool University Press, 188 pp.

Earlier this year the National Museum of Scotland staged a major exhibition of the career of fashion and interior designer Bernat Klein. Although Serbian-born, Klein became synonymous with the Scottish Borders where he established a textile business in Galashiels and lived nearby in one of the finest example of domestic modernist architecture still extant in Scotland. High Sunderland was commissioned by Klein from Yorkshire architect Peter Womersley in 1955 and was one of a number of cutting-edge houses (there were a lot of edges to them) designed by Womersley from the 1950s into the 1970s.

Published in Womersley’s centenary, Neil Jackson’s meticulously researched monograph is a both a biography of the architect’s life and a lavishly illustrated guide to his imagination as represented by the buildings he conceived. The tragedy is that while High Sunderland survives, many others have either been substantially altered or demolished. Port Murray House at Maidens on the Ayrshire coast, with its beautiful white Sicilian marble floor, cedar wood walls and floor to ceiling windows, should never have been allowed to fall into such a state of disrepair that it had to be demolished.

Womersley’s talents were by no means limited to domestic design. The brutal but stunning Nuffield Transplant Unit in Edinburgh is his, as is the unique grandstand at Gala Fairydean Football Club. It is to be hoped that the Bernat Klein Studio, built in 1972 within walking distance of High Sunderland, does not go the same way as Port Murray House.

Womersley should be remembered as one of the great 20th century British architects along with Denys Lasdun and Basil Spence. In 1958 the latter was asked to name the best modern house in Britain: he replied, “Any house designed by Peter Womersley”.

The Fraud by Zadie Smith Hamish Hamilton, 455 pp.

Never judge a book by its cover, so they say. But the cover for Zadie Smith’s first historical novel is the reason I bought it. Designed by gray318, it’s like an old handbill and while at first glance appears unremarkable, on further inspection, maybe not so much. There are five typefaces used, fonts belonging from one word swapped with others, all slightly out of alignment, just a bit unsettling.

Which presumably, is exactly the desired effect. There’s a lot in here, the novel’s central character Eliza Touchet is cousin to the once-famous, now almost forgotten, novelist William Ainsworth. Then there’s Andrew Bogle who grew up enslaved in Jamaica. Charles Dickens makes an appearance too. And the background to all this is the ‘Tichbourne Trial’, which from April 1873 to February 1874 is still one of England’s longest criminal trials.

It's a huge undertaking, a late 19th century epic, but Zadie Smith weaves all the parts together, the short chapters working particularly well, making it seem less heavy handed than it could easily have been in the hands of another author.

How to Build a Stock Exchange by Philip Roscoe Bristol University Press, 207 pp.

Philip Roscoe’s history of stock exchanges is the third book I have read this year which references the Zong Massacre of 1781 in which Captain Luke Collingwood of the slave ship Zong ordered the drowing of 133 slaves while crossing the Atlantic. This terrible episode in the practice of slavery that Britain had done so much to establish is also described in Swing Time (Zadie Smith, 2016) and Tremors (Teju Cole, 2023). The slave trade was part of the Liverpool stock market and the men were drowned in order to restrict the owners’ losses. It is one of many examples - the US government’s bailout of AIG in 2008 being another - that Roscoe uses to illustrate how stock exchanges play a central role in our lives, even if we have no direct relationship with them.

Zippily written, especially when it comes to the massive changes that took place in the financial markets both in here and in the USA during the 1980s and early 1990s, this is - if nothing else - a fascinating social history.

Confessions of a Highland Art Dealer by Tony Davidson Woodwose Books, 267 pp.

Man buys derelict Highland church and - after much hard work - converts it into a flourishing art gallery. That in itself would make for an interesting read. But there’s a lot more here than the story of Tony Davidson’s Kilmorack Gallery near Beauly, which he has now been running for a quarter of a century, 25 years in which he reflects on the changes from an analogue to an internet society.

Although born in Edinburgh Davidson clearly has an affinity with the North East of Scotland. Some of his descriptions of the countryside, his relationship with it and his feelings for it border on the poetic. Anyone expecting Shaun Bythell type tirades at customers will be disappointed. Not a straightforward memoir by any means and so much the better for not being so,

Watford Forever by John Preston Viking, 295 pp.

The subjects of John Preston’s last two books were the sex scandal that ended the career of Jeremy Thorpe (A Very English Scandal, 2016) and the rise and fall of Robert Maxwell (Fall, 2020). In Watford Forever he continues his exploration of Englishness - in Robert Maxwell’s case, an aspiration only - with the extraordinary story of how Graham Taylor and Elton John dragged a football club from obscurity to the very top: second place in Division One, three rounds of the UEFA Cup and the 1984 FA Cup Final.

The action starts slightly before I became interested in football and decades before, through choice, I would listen to the music of Elton John. And although I did know that Elton had - at some point - bought Watford F.C., what I didn’t realise was that he had a passion for football since he was a kid, watching Watford from the terraces with his father, and that his later involvement with the club was far more than being a figurehead or just throwing money at it. It was Elton who sought out and persuaded the then up-&-coming young (much later, England national) manager Graham Taylor to move from Lincoln F.C. to Watford.

It's difficult to pinpoint when one era of history ends and another begins, but if there ever was a golden era of English football then it ended, or began to end, somehere within the pages of this book. This is a landscape unrecognisable from the UAE and Saudi investment vehicles that masquerade as the beautiful game today.

What comes over in this sympathetic portrayal of the parallel careers of Graham Taylor and Elton John is their friendship and the respect that they had for each other. Elton credits Taylor with putting him on the road to recovery after years of alcohol and cocaine abuse. Taylor describes Elton as the younger brother he never had. On Taylor’s death in 2017, Elton had this to say “[Graham and I] shared an unbreakable bond since we first met. We went on an incredible journey together and it will stay with me for ever.”

If you're buying any of these books then please shop local, they need the business more than Amazon. In Edinburgh my favourites are the Edinburgh Bookshop, Golden Hare and Toppings.